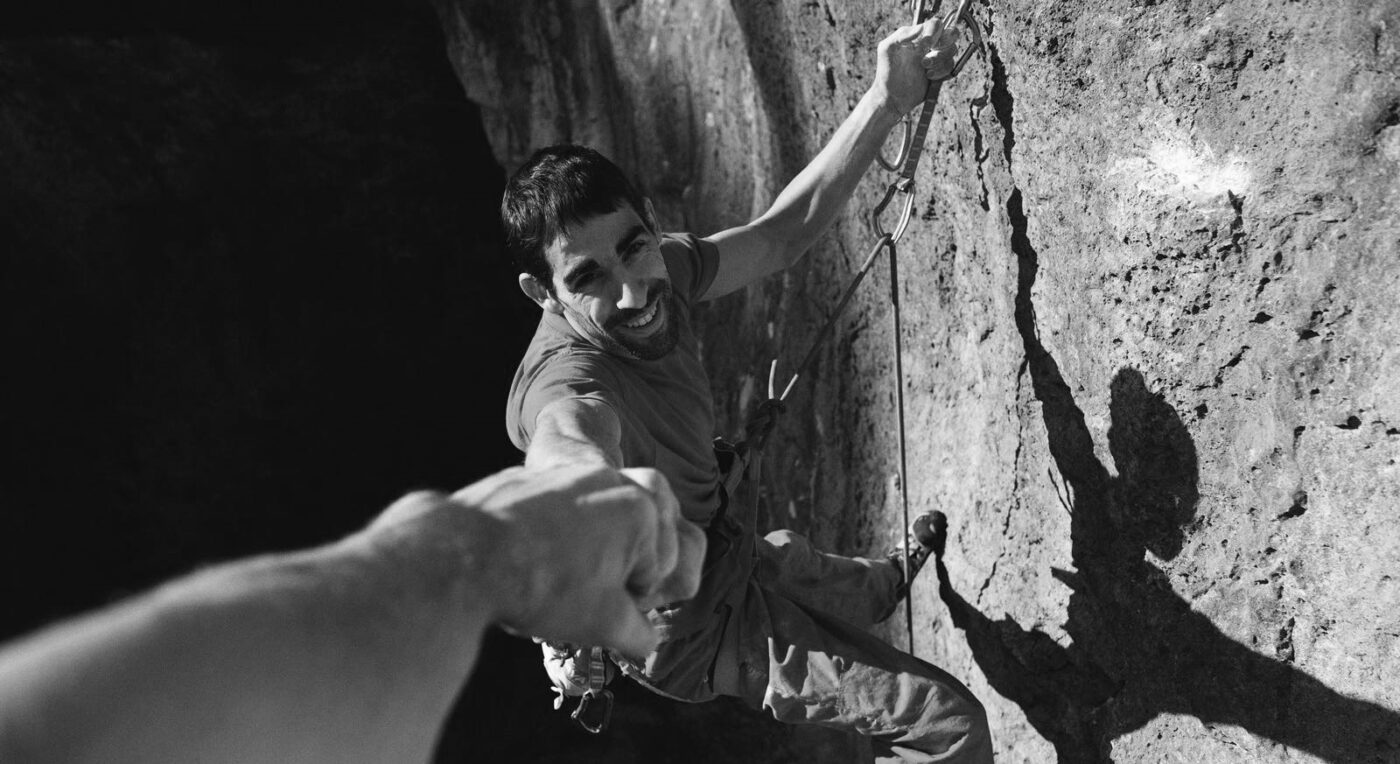

The Sensei: Uri Maraver

How the martial arts expert brings his experience and values to climbing.

por tenaya

2023-01-17T20:51:58

Uri Maraver has deep roots in the world of martial arts. He studied, trained, and competed in Judo from a young age, all the while the draw of the mountains grew stronger. Soon enough the Spanish athlete was hooked on climbing. He discovered that the skills and values he learned on the tatami mats translated well to the rock.

Maraver climbed sporadically at first, he says, but his devotion to this newfound passion continued to swell. He joined the Centre de Tecnificació d’Escalada Esportiva de Catalunya (CTEEC), and for a time, tried to balance both Judo and climbing, but dividing his energy and focus became a challenge. Eventually, climbing won the fight. He was a full convert. At the CTEEC, Maraver progressed from an athlete into a coaching position where he could share his experience with both sports and the values he learned through martial arts with the next generation of climbers.

Here, Maraver speaks on his Judo roots, how they translate to climbing, and what it takes to be a top athlete in today’s competition landscape.

Q&A with Uri Maraver —

What inspired you to become an athletic trainer?

From a very young age I practiced Judo. After years as an athlete, I felt committed to go a step further and try to convey what is, for me, the feeling of the activity as a way of life. I received special training and education in Judo, not only as a coach, but also with a focus on the human element. Through the ups and downs, this sport and the people around it have inspired me to share these experiences with others and the next generation.

How has your background in Judo influenced you?

Studying Judo at a high-performance sports center made me realize there are many aspects to consider for overall performance, both in Judo and in climbing. Needless to say, one of the most important is the number of hours spent practicing and analyzing it. If you don’t put in the time, you’ll never be able to reach your full potential—it’s as simple as that.

The time I spent at the “CAR” (Centre Alt Rendiment) in Sant Cugat (Barcelona) as a teenager was a very good experience, but also hard. All of my energy was devoted to sports and, of course, to academic training, an aspect that we can never neglect when working with young people, whatever the demand level is for sports activity. Being able to see and share experiences with the best Spanish athletes from all the Olympic disciplines left a powerful impression on me. These athletes impressed me with their physical abilities, and especially their mental capabilities.

How did you discover climbing, and why did you eventually transition from martial arts to rock?

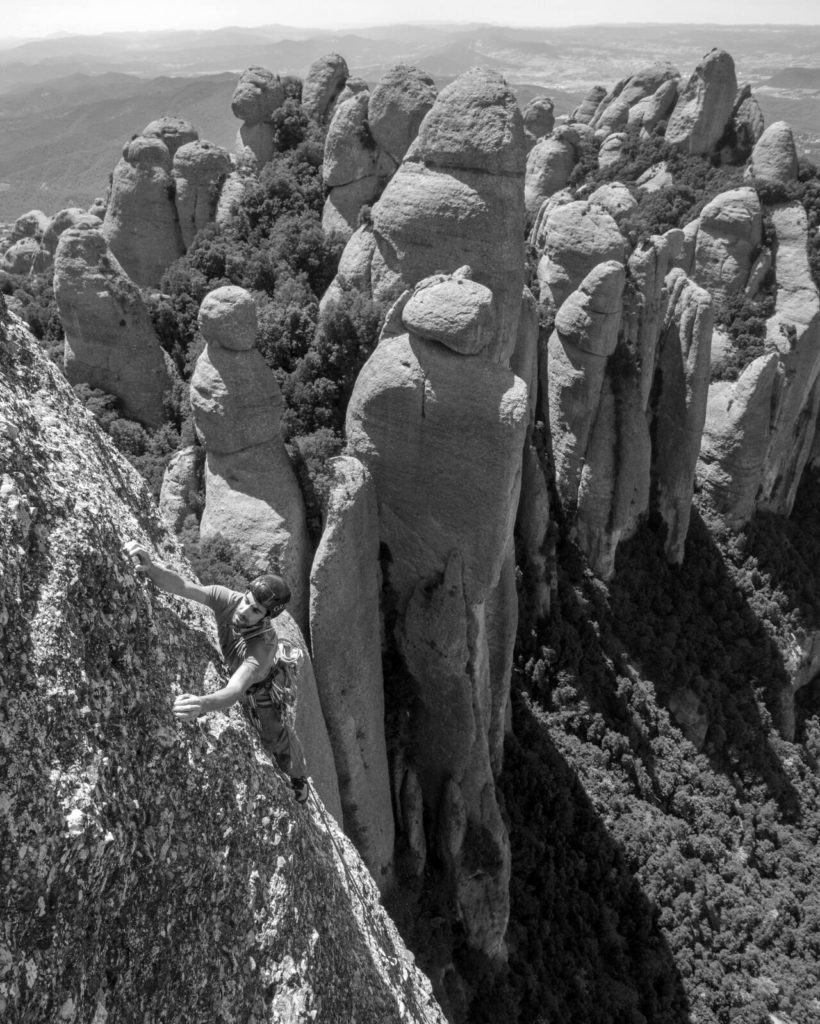

From a very young age I loved being in the mountains and spent time outdoors with my family. Whenever I could, I went with friends around the village and to the Pyrenees. Little by little I met people from the hiking club of my village. I became a member and went out every weekend I was free from judo competitions.

I loved going out in the mountains, and whenever I saw people climbing, I thought to myself, that’s what I really want to do. So, I looked for people to start climbing with—and from day one it captured me. For the first few years I climbed sporadically, and I even dared to accompany friends in competitions. After a while I became part of the Centre de Tecnificació d’Escalada Esportiva de Catalunya (CTEEC), but still could not focus all my attention on climbing, as I was still in the “CAR” and focused on Judo.

Years later I put aside the tatami and devoted more energy to climbing. After a few seasons at the CTEEC as an athlete, I had the opportunity to be part of the training team, trying to take advantage of all the hours of experience I had accumulated on the tatami mats and climbing walls. Since then, I have not stopped sharing time with young and not so young climbers to try to help them improve as athletes.

Is the training you received as an athlete similar to the way you coach others now? If not, how has it evolved?

Well, the truth is that the way I coach climbers looks more like the training I had in Judo than in climbing. The first coaches I had as a member of the CTEEC have also greatly affected my career as a climber, further reinforcing the values I had grown up with in Judo, such as courage, honor, modesty, respect, self-control, and friendship. These values marked my path when I started climbing, and I try to pass these along to my athletes. Along with a culture of effort, these values are the foundation of my training, ensuring mutual commitment, and positive motivation and attitude.

What’s the difference between a coach and a trainer?

A coach is said to be the person in charge of giving instructions and correcting behaviors in training, but it is very difficult for a good coach not to be a better trainer or educator. Educating is part of the job, especially when we’re dealing with young people, since we want to cultivate good behaviors in them. It’s important to not only think of them as athletes, but also as people. The first phases or years are when the foundations of an athlete’s career are laid, so the figure of the trainer is crucial to mark the values and guidelines of the activity.

What does a climber need to perform well?

In my opinion, a climber needs a good sports base and devoted mentors, accompanied by a good atmosphere of tranquility where there is not much pressure to perform. It is very important that the climber maintains motivation, but that must come from the environment and oneself, where the desire to excel and constantly improve is intrinsic, as opposed to external elements.

If the athlete is surrounded by a relaxed atmosphere and can focus on the activity, he will be able to give 100 percent. Good advice and good facilities will also be the key to carry out the training to match the athlete’s objectives, which should be set with optimism but with realism, considering the resources at your disposal.

“A climber needs a good sports base and devoted mentors, accompanied by a good atmosphere of tranquility where there is not much pressure to perform.”

What explains the success or mastery of certain climbing schools throughout history (Austrian, French, Slovenian, Japanese, etc.)?

I think it has a lot to do with the roots of the activity and culture of the sport in certain countries, as some are more committed to the sport at schools from as young as primary education. Also, in some areas of the world, such as France, the mountains have always played an important role in tradition.

In the competitions we are seeing how the general performance of some countries is increasing, both in terms of results and in the number of athletes who can reach the top of the ranking. Some of the countries you mentioned have been working for years with many youngsters. There is no secret—the bigger the base on which you work with, the more athletes and the higher level the country will achieve over time. The overall results will be directly correlated to the resources allocated to raising the level of sport.

What demands will we face in the future of climbing?

Climbing is still a very young sport, and we still have a long way to go and a lot to learn. We should look at other sports with a broader history and try to learn from them to meet the challenges that might lie ahead. We’ll need more resources, more facilities, and more commitment from the institutions to be able to raise the level of our athletes and to be able to play an important role in the future of climbing.

Being in Spain where we have so much to climb and a solid trajectory, it would be a shame to miss this opportunity. Climbing is a never-ending challenge, so we must be prepared to make the right decisions and face the changes that come.

Climbing will be in the Olympics for the first time in Tokyo. What will that mean for the sport, as a whole?

Finally, we will see that climbing is not only a simple activity that consists of getting to the top of mountains, or walls, or boulders, but has evolved into an official sport with a specialized branch of professional athletes.

Being an Olympic sport will make the activity visible all over the world and will surely give a boost to countries where climbing is not yet well developed. As a result, we will also see an increase in the number of climbers, which will likely bring many benefits, and also some growing pains, such as more crowding at the crags.

Another thing we will certainly see will be a progression in difficulty, with climbers reaching new grade levels, both in bouldering and in sport climbing.

We’ve seen the best outdoor rock climbers continue to dominate in the World Cup competitions. Do you think that will continue, or will competition climbing become a specialized niche?

It is true that until now the best rock climbers have dominated the landscape of competition climbing. But it is also true that they have increasingly focused more energy on training and competitions than on real rock. Ahead of the Tokyo Olympics, we saw how many of the top climbers focused on qualifying and put outstanding projects on the backburner.

With the arrival of the Olympics, competition climbing has become even more competitive, which makes it harder for rock climbers to achieve good results without being as focused as possible on competitions. Moreover, it is very difficult to compete in three different disciplines—boulder, lead, and speed—at a high level without investing much time in specific training.

I think it will be increasingly difficult for athletes to combine good results in competitions and also on the rock in a single season. We are seeing this in recent years where most of the athletes who reach finals or land on the podiums are from Asian countries or Central Europe, where they hardly climb outdoors.

Surely, in the next Olympics in Paris without the combined format, we will see an improvement and greater specialization in athletes.

“We’re seeing a kind of professionalism that makes an individual advance from a climber to an athlete.”

How do we transition from understanding climbing as an activity to climbing as a sport?

Climbers of the next generations are changing. Many now focus on performance above everything else, incorporating daily workouts, new nutrition habits, and psychological work into their climbing. We’re seeing a kind of professionalism that makes an individual advance from a climber to an athlete. Whether it’s to compete or simply to climb a specific route, or boulder, or grade, people incorporate many tools to achieve their goals. This means that climbing, at least for some, is transitioning from a fun phase to a sportier one.

As a trainer, what qualities do you look for in your climbers?

A slow, but steady evolution and the desire to excel day by day. It is very gratifying to see how they always face a personal or sporting difficulty with a good attitude and quick decision making.

It’s amazing what I learn from them all. I’m impressed by their abilities to turn situations around. I often think my climbers, my students, are one step ahead of me, and as a teacher that makes me want to keep climbing and sharing with them. My climbers personify passion—a great source of my motivation!